Trial preparation and pre-trial research play pivotal roles in achieving successful outcomes in legal cases. The ability to gather insights from potential jurors and refine trial strategies based on carefully conducted and scientifically validated research is crucial. The use of focus groups and mock trials are some of the most traditional approaches to trial preparation and, as we discussed in a previous article (“Types of Focus Groups and Their Purpose”), these methods can take many forms. Traditionally, in-person focus groups have been the go-to method for pre-trial research. However, that is changing with the rapidly evolving landscape of this digital age in which methods of collecting data online are vastly improving and expanding. Alternatives that capitalize on these methods include virtual focus groups (VFG). There are many benefits associated with using VFGs in this context, which we have outlined in a previous article (“Virtual Focus Groups Benefits”). However, the present article aims to explore the unique characteristics of an under-utilized version of the VFG: the async online focus group (AOFG). We will explore the utility of AOFGs for pre-trial research, discussing the advantages, considerations, and best practices for implementation.

VGFs can be conducted in real-time or asynchronously. The promise of VFGs has become increasingly intuitive for many people, as the world continues to adapt to virtual work. VFGs simply bring the traditional, in-person format online, much like the shift from in-person work to virtual work that has characterized much of American life in recent years. However, more recently AOFGs have emerged as a valuable tool that are distinct from other types of focus groups in format, breadth, and reach.

Overview of Async Online Focus Groups

AOFGs are a dynamic and flexible research method conducted on digital platforms. Unlike traditional in-person or synchronous virtual focus groups, AOFGs are not conducted at one specific, pre-arranged time. Previous research that has evaluated virtual groups have concluded that the method is not only viable, but often superior to traditional focus groups in terms of sample size, cost efficiency, and research outcomes [1]. Murray concluded his assessment by stating:

“The use of VFGs [virtual focus groups] has provided valuable research data that could have not been readily obtained using other methods and from participants whom I could not have otherwise hoped to gather together for discussions without considerable expense.”

However, traditional focus groups and virtual focus groups share one important, often prohibitive limitation. Specifically, they both limit the sample significantly by requiring participants to have a mutually suitable time available and reliable transportation to get to a physical location. Additionally, as Fox, Morris, and Rumsey [2] noted, synchronous virtual focus groups are disproportionately suitable for participants comfortable contributing to an online environment. For those who are less comfortable navigating an online environment, the fact that data collection is occurring in real-time can be too quick paced for those unfamiliar with the technology.

Limitations of Other Methods

One of the most important considerations in any research, qualitative or quantitative, is ensuring that you are collecting your data from a representative sample. This is a problem for both in-person focus groups and synchronous VFGs which favor only potential jurors who are available during specific hours, who have access to reliable transportation, and who are technologically savvy enough to participate in a fast-paced online environment in real-time. Essentially, these methods are ignoring important swaths of the population. This not only means you are likely going to end up with a homogenous focus group likely to have less productive discussions, but you are creating a sample that will not resemble the actual jury that you are trying to understand.

The famous image of a newly elected Harry Truman holding a copy of the Chicago Daily Tribune with the headline “Dewey Defeats Truman” was the result of notoriously erroneous polling based on unrepresentative sampling. Researchers conducted their polling via telephone, which meant only people with a telephone were polled. In 1948 the people with telephones were disproportionately wealthy and Republican. If you conduct a poll of mainly Republicans, naturally that poll will suggest that the Republican candidate would win. To construct a valid sample, you carefully consider the factors that may lead you to only hear from specific subgroups of people that do not represent the diverse population you are interested in. By conducting focus groups during working hours, requiring that your participants have access to reliable transportation or reliable Internet connection, you may be conducting focus groups that are leading to your own erroneous headline that “Plaintiff Defeats Defendant”, that may turn about who will be defeating who in a trial.

Advantages of Asynchronous Online Focus Groups

AOFGs overcome these limitations by allowing participants to provide their input at their convenience. Jury research firms that specialize in this approach, such as Jury Analyst, are able to create customized online platforms that offer an engaging and interactive experience that resembles popular online communities like Reddit. AOFGs share the same advantages as VFGs in the sense that they are accessible and cost-effective, but their unique format imbues them with other distinct advantages:

- Flexible Participation is Diverse Participation: As we mentioned in our discussion of the limitations of other methods, perhaps the key advantage of AOFGs is that they greatly expand the types of participants who are able to provide their feedback. AOFGs allow participation from anyone with even intermittent access to the Internet to participate. This opens participation to a range of people who otherwise could not participate, including those with professional or familial obligations, health concerns, or transportation limitations.

- Real-Time Data Collection, Eliminates Need for Transcription: Other types of focus groups must rely on verbal communication during data analysis. This is not only time-consuming but opens up the possibility for human error during transcription. In comparison, AOFGs use written communication during data analysis. Some feel that by eliminating in-person participation, you lose the ability to assess participants’ body language and other nonverbal cues. However, the lack of nonverbal communication seems like it may turn out to be a benefit for interpretation, rather than a hindrance [3]. The participants are aware they are limited to the contents of their written communication and seem to actually compensate for this by adding more elaborate, explicit descriptions during written communication than during verbal communication. Obviously, explicit and objective written data is much easier to interpret than the subtle, implicit nuances of verbal communication. Additionally, participants seem to prefer written communication in general [4]. Not only that, but returning to our point about representative samples, people who have difficulty expressing themselves verbally, whether due to social, cognitive, or health reasons, can be included in data collection and have a much easier time participating [5].

- Anonymous Responding: Another benefit of participating on an online platform rather than in-person or over Zoom, is that it is possible to ensure participant anonymity. People are much more comfortable sharing information, especially sensitive information, when they are able to respond anonymously. [6]. Not only will participants be more likely to share more information, but the information that they do share is more likely to be accurate. When there is no face-to-face component in a focus group, there is less of a desire to present oneself in a socially desirable way [7]. The moderator is also anonymous, which eliminates another study design concern: experimenter effects. A good focus group moderator must make sure they present themselves as completely neutral, so as not to not bias how participants will respond. Failures to achieve this can occur even through a moderator’s nonverbal cues, like a moderator excessively nodding and thus steering participants towards what they now perceive as the “correct” answers [8]. In an AOFG, the moderator can carefully consider their responses to ensure they contain neutral language, and they no longer have to carefully monitor their nonverbal behaviors. Even in the absence of procedural errors that can lead to biased focus group participation, a moderator’s personal characteristics (e.g., age, sex, race, appearance) can affect the behavior of participants. By allowing the moderator to remain anonymous, you are able to remove yet another source of possible confounds.

- Mitigating Negative Group Dynamics: In-person and synchronous VFGs are subject to the complicated psychology of group dynamics. Certain personal factors can lead to one member of a focus group completely dominating the discussion [9]. More introverted members of a focus group may either not have a chance to share their opinions or will not feel confident sharing their opinions even if given the chance if it deviates from the opinions of the dominant group member. The format of an AOFG lends itself to more equitable, balanced, and honest responding that gets around issues of self-presentation and self-disclosure. Even for focus group members who have no reticence about sharing their opinions, some people simply take longer to think through an issue and formulate a thought. Face-to-face discussions are fast paced, but AOFGs provide a space for all participants to have sufficient time to come up with a carefully thought-out response [9].

- Dynamic Question Development: Another unique advantage of AOFG is the ability to adapt the questions in real-time based on how participants are responding. Unlike face-to-face focus groups, where the sequence and order of questions are predetermined, AOFG platforms allow for flexibility and immediate adjustments. As participants engage in discussions and share their perspectives, an entire team consisting of not just the moderators, but behavior analysts, attorneys, and data scientists can work together to closely monitor the conversation and identify emerging themes or areas that require further exploration. This adaptability enables researchers to delve deeper into specific topics, probe for clarification, and gain a more comprehensive understanding of jurors’ viewpoints. By leveraging the dynamic nature of AOFGs, you can maximize the richness and depth of the data collected.

Considerations and Best Practices

To conduct effective AOFGs for the purpose of pre-trial research, several considerations and best practices should be kept in mind.

- Recruiting: It is critical to carefully select participants to ensure diversity in demographics and experiences, which can provide a comprehensive understanding of potential jurors’ perspectives. Thoughtful recruiting strategies, such as partnering with reputable research firms or utilizing online panel providers, can help achieve this goal. Refinement of these recruitment strategies so that we arrive at representative jury-eligible samples within a specific location is one our specialties at Jury Analyst. The format of the AOFG lends itself to the selection of a more representative sample by meeting the audience where they are. However, it is important to be aware of common pitfalls during recruitment that can lead to the creation of a biased sample. For instance, platforms like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) can be used to gather large amounts of data quickly, but the people completing these surveys are “professional respondents”. This means that your participants are more likely to be prone to survey fatigue, to respond in way they think the researcher wants them to respond, to speed through the survey, and probably the issue that is most concerning for jury research, to circumvent the location requirements [10]. Our team’s extensive experience with research design considers these and other recruitment concerns. We ensure that the samples we use are representative, unbiased, and have withstood comprehensive screenings and background checks.

- Focus Group Design: The design of the AOFG format, question design, and creation of an efficient and accessible online platform for discussion all play a vital role in stimulating meaningful conversations. Our team of experts at Jury Analyst are highly skilled with both qualitative and quantitative study design and analysis.

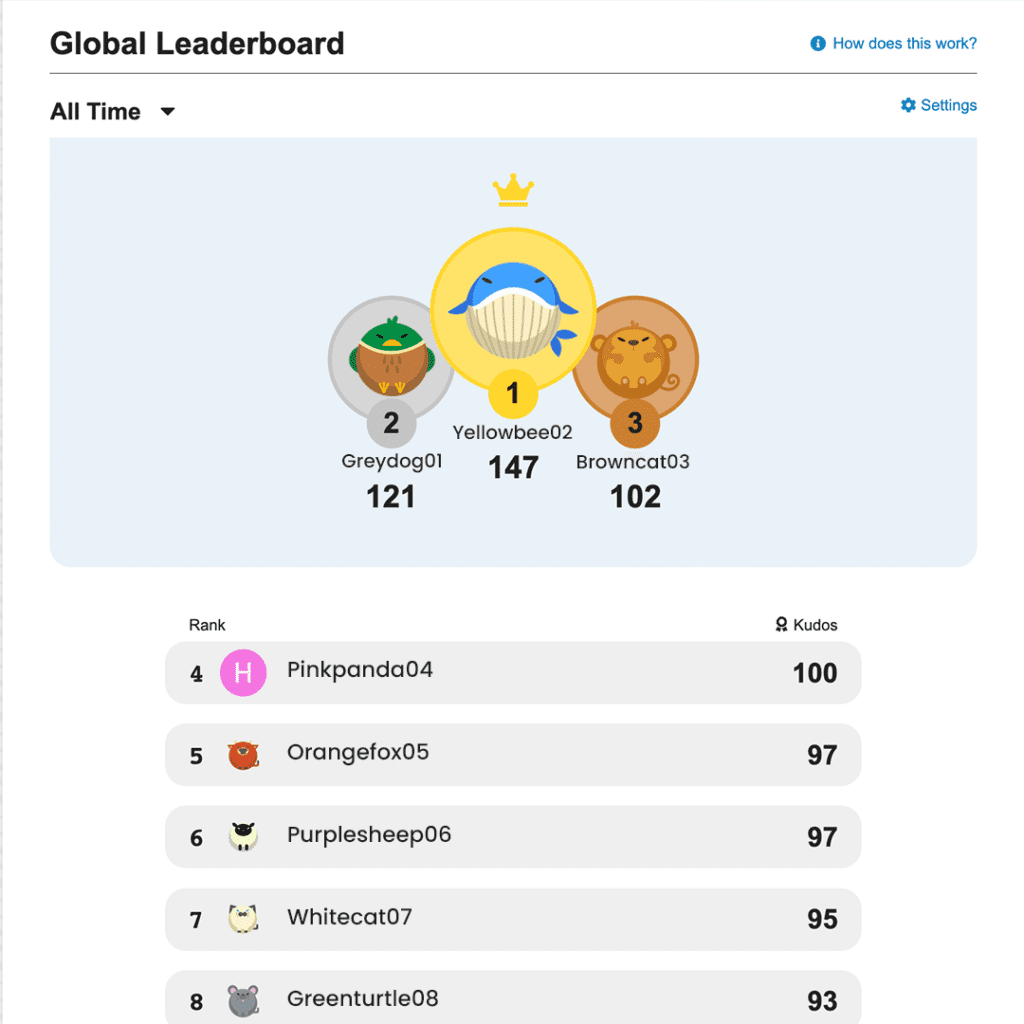

- Enhancing Engagement: One concern about the format of an AOFG is that participants do not benefit from the immediate feedback and social dynamics that can enhance engagement in a traditional focus group. Asynchronous formats can lead to a sense of detachment, which may result in lower levels of active participation. Fortunately, the shift to online, asynchronous learning that was necessitated by the COVID pandemic led to a significant amount of research on the topic of creating incentives in asynchronous environments that foster active participation. One promising strategy for accomplishing that goal is gamification, or the application of game mechanics and technology to non-game spaces [11]. Gamification of asynchronous spaces has been found to increase the level of engagement, retention, and intrinsic motivation of participants [12, 13]. We have applied the gamification framework to the development of our Async dashboard. Specifically, we tap into participants’ intrinsic motivation by incorporating game-like elements like leaderboards, achievements and rewards. In our experience this has been effective for incentivizing participation, fostering a sense of collaboration amongst participants, and promoting more elaborate responses to the posted questions.

- Moderation: Managing the asynchronous nature of the AOFG requires active moderation to ensure participants are engaged, encourage productive dialogue, and address any conflicts that may arise. Our behavior analysts’ psychological training affords them an awareness of the various considerations that go into creating an environment that both encourages disclosure and depicts neutrality.

- Analysis: Analyzing the data from AOFGs requires a unique set of skills, combining expertise in psychology and statistics. Our team of behavior analysts, equipped with their doctoral training in both disciplines, is particularly well-suited for that task. Understanding human behavior, attitudes, and biases allows for deeper assessment of the nuanced responses and underlying themes expressed in the AOFG discussions. Moreover, statistical expertise enables our team to employ rigorous quantitative analysis techniques, such as content analysis or thematic coding, to identify patterns, categorize responses, and extract meaningful insights from the vast amount of qualitative data generated by these focus groups. By leveraging interdisciplinary knowledge and analytical skills, behavior analysts can provide comprehensive and evidence-based interpretations of qualitative data.

Integration with Other Research Methods

While we have outlined the unique advantages that AOFGs have to offer, in our view this approach is not a replacement for other research methods commonly used in trial preparation. Instead, we prefer a mixed-methods approach to pre-trial research that harnesses the strengths of each respective method. By using multiple, complementary methods, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of potential jurors’ perspectives. For instance, by conducting in-person and virtual focus groups we can collect data from real-time interactions and non-verbal cues that AOFG may lack. Additionally, we conduct quantitative research like surveys that enable large-scale data collection and statistical analysis. This mixed-methods approach allows us to leverage the strengths of each approach and obtain a more holistic view of the data.

Conclusion

The emergence of AOFGs as a valuable tool for pre-trial research opens up new possibilities for trial consultants in the digital age. By taking advantage of the latest findings from behavioral and data science, it is possible to collect and obtain an entirely unique vein of rich qualitative data. With the ongoing evolution of digital platforms and the increasing acceptance and refinement of online methods, AOFGs are poised to play a crucial role in the future of pre-trial research.

References:

- Murray, P. J. (1997). Using virtual focus groups in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 7(4), 542-549.

- Fox, F. E., Morris, M., & Rumsey, N. (2007). Doing synchronous online focus groups with young people: Methodological reflections. Qualitative Health Research, 17(4), 539-547.

- Williams, S., Clausen, M. G., Robertson, A., Peacock, S., & McPherson, K. (2012). Methodological reflections on the use of asynchronous online focus groups in health research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 11(4), 368-383.

- Turkle, S. (2011). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other. Basic Books.

- Tanis, M. (2007). Online social support groups. In A. Joinson, K. McKenna, T. Postmes, & U. Reips (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of Internet psychology (pp. 139-153). Oxford University Press.

- Ybarra, M. L., Espelage, D. L., Valido, A., Hong, J. S., & Prescott, T. L. (2019). Perceptions of middle school youth about school bullying. Journal of Adolescence, 75, 175-187.

- Bargh, J. A., McKenna, K. Y. A., & Fitzsimmons, G. M. (2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the “true self” on the Internet. Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 33-48.

- Harrell, M. C., & Bradley, M. A. (2009). Data collection methods: Semi-structured interviews and focus groups. RAND Corporation Technical Report Series.

- Smithson, J. (2000). Using and analysing focus groups: Limitations and possibilities. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 3(2), 103–119.

- Ahler, D. J., Roush, C. E., & Sood, G. (2019). The micro-task market for lemons: Data quality on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Political Science Research and Methods, 1-20.

- Law, F. L., Kasirun, Z. M., & Gan, C. K. (2011, December). Gamification towards sustainable mobile application. In 2011 Malaysian Conference in Software Engineering (pp. 349-353). IEEE.

- Jarnac de Freitas, M., & Mira da Silva, M. (2023). Systematic literature review about gamification in MOOCs. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 38(1), 73-95.

- Behl, A., Jayawardena, N., Shankar, A., Gupta, M., & Lang, L. D. (2023). Gamification and neuromarketing: A unified approach for improving user experience. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 1-11.