Trial lawyers are keenly aware of how crucial a role that the composition of a jury plays in determining the outcome of a trial. In order for the legal process to successfully uphold the ideal of a defendants’ right to a fair trial, jurors must evaluate the evidence that informs the verdict in a fair and impartial manner. However, a considerable obstacle exists between the psychological reality of human cognition and the ethics of an equitable legal system. As much as we would like to believe that the immense responsibility of deciding someone’s legal fate would ensure that jurors remain objective and free of bias, this idealistic expectation conflicts with the psychological reality of decision-making. That is not a critique on the ethical constitution of jurors, but rather an acknowledgment that jurors are human beings and, just like all human beings, are prone to the self-deception that results from our hidden biases.

One of the most resilient and robust of these hidden biases is confirmation bias. In legal contexts, confirmation is particularly relevant as it can significantly influence jury selection and the overall fairness of the legal process. In this article we will delve into this striking feature of human nature, exploring the psychological underpinnings of confirmation bias and shedding light on its impact within the legal system,

Understanding Confirmation Bias

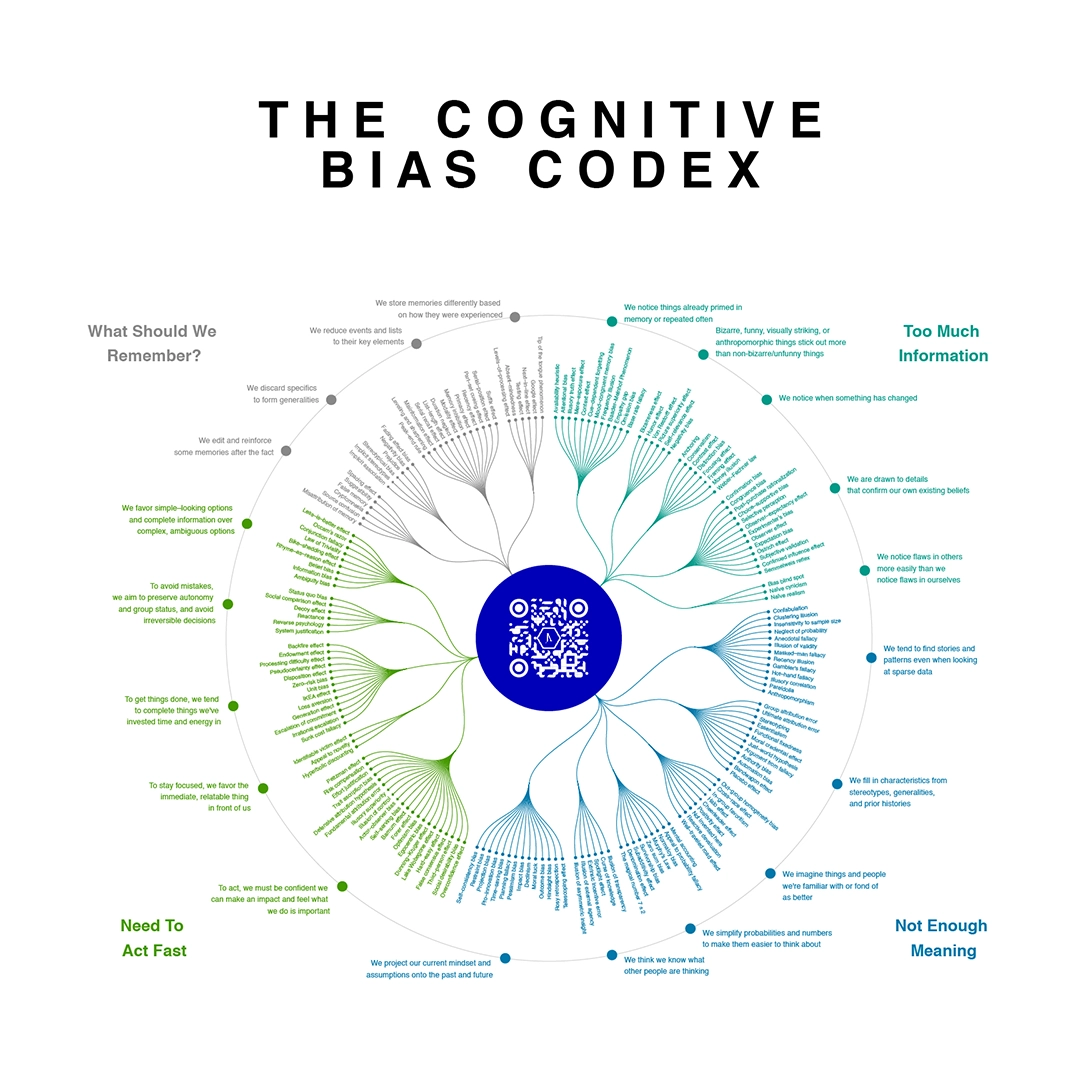

Confirmation bias refers to our inherent tendency to seek, interpret, and create information that verifies existing beliefs and opinions while disregarding or downplaying contradictory evidence. Confirmation bias is known as the “mother of biases” due to its pervasive influence and the importance of counteracting it. This pervasiveness can be attributed to how easily, unintentionally, and without our awareness, confirmation bias can fool us into thinking what we expect to see [1]. Confirmation bias explains why it often feels futile to argue politics with someone with a different viewpoint; you can construct the best argument in the world, and it won’t override a person’s drive to maintain their beliefs.

Confirmation bias may feel commonsensical when it comes to politics; it is easy to understand that beliefs that are a point of pride, identity, or identity would be difficult to give up. What is more surprising is that people cling to their pre-existing views even to their detriment. What about a trial lawyer who relies on false stereotypes for jury selection, even after being presented with evidence that that approach has been shown to lead to inaccurate conclusions [2]? Accepting a scientifically validated approach to jury selection would benefit the trial lawyer by leading to improved trial outcomes, yet doing so would also mean upending their previous belief about what makes a good or bad juror. Once again, the drive to maintain your beliefs prevails. It does not matter whether viewing things through the lens of your preconceptions leads to positive or negative outcomes for yourself; in either case, people exhibit belief perseverance, clinging to their initial beliefs even after being discredited.

Confirmation bias is not an individual criticism akin to calling someone stubborn or close-minded. It is the product of our brain’s efficiency-seeking mechanism, which exists to cope with our limited cognitive capacity [3]. The resulting cognitive shortcuts, like confirmation bias, are useful adaptations but can sometimes lead to errors in judgments. Confirmation bias is a fact of human nature; therefore, it is not limited to a particular ideology or perspective; it affects individuals across diverse backgrounds and beliefs.

Confirmation Bias in Legal Settings

The legal system naturally places a high premium on unbiased decision-making, ensuring fair and just trial outcomes. However, confirmation bias can subtly infiltrate jury selection and significantly impact the fairness of the trial process. The only way to overcome and compensate for confirmation bias is to recognize the biases a person possesses and the situations in which confirmation bias is most likely to exert its influence. Only by addressing confirmation bias and adopting procedural safeguards can legal professionals effectively mitigate its more pernicious effects to enhance the objectivity and integrity of the legal system.

Factors Influencing Confirmation Bias in Jury Selection:

- Pre-existing beliefs and attitudes of potential jurors: Individuals bring their personal biases and perceptions into any decision they make, including while serving as jurors. These pre-existing beliefs can color their perception and evaluation of the evidence. Consider a juror who believes that people of higher socioeconomic status are more credible than people of low socioeconomic status. If you are a plaintiff attorney representing someone from a lower socioeconomic background against an affluent defendant, it would not matter if you presented evidence to challenge those expectations. Confirmation bias means that the juror’s expectations about your client’s credibility will overrule any evidence presented to the contrary.

To demonstrate why this is the case, consider one study that asked participants to evaluate the academic potential of a 9-year-old girl named Hannah [4]. Participants were divided into two groups. Group 1 was told that Hannah was raised in an affluent community by college-educated parents, both employed in professional settings. Group 2 was told that Hannah grew up in a run-down urban neighborhood and that her parents were uneducated blue-collar workers, creating low expectations. Unsurprisingly, the conditions presented to Group 1 created more positive expectations that led to higher evaluations of Hannah’s academic potential. What was surprising was how these evaluations were affected by the exact same evidence. Participants in each group were shown a video of Hannah taking an academic achievement test and doing about average, missing some easy questions but also getting some difficult questions correct. After viewing this evidence, Hannah received much lower evaluations from the participants who thought she was poor and much higher evaluations from those who thought she was rich. The same evidence was interpreted in the opposite direction depending on the participants’ expectations before seeing the evidence.

This illustrates that virtually no type of evidence can easily penetrate confirmation bias. A person’s pre-existing beliefs will be verified by consistent evidence, unaffected by inconsistent, and fueled by mixed or ambiguous evidence. In any scenario, the pre-existing belief, not the evidence, will impact the conclusion.

- Media influence and pre-trial publicity: Media coverage can shape public opinion and influence potential jurors, potentially reinforcing existing biases. If a juror hears information about a trial before the case, the reporting will serve as a pre-existing belief that will distort how they interpret any evidence or facts presented at trial. Sensationalized media reporting or biased portrayals of defendants can sway jurors’ perceptions before they even set foot in a courtroom. It is important to note that it is no longer the case that high-profile cases are the only cases affected by pre-trial publicity. Whether or not the case was discussed on the news is only one avenue for exposure. Any person involved in a trial can be discussed on social media; thus, there are many more opportunities for a juror to be exposed to biasing information. Studies of mock jurors indicate that pre-trial publicity’s effect persists despite a judge’s explicit instructions to disregard it [5]. If we assume people do not mindlessly consume pre-trial publicity but engage with case coverage and use that to formulate an opinion about a person’s guilt or innocence, then it is likely that jury deliberation will be impacted by confirmation bias. Confirmation bias, as we have seen, occurs not only with deeply held, personal beliefs but even with more passingly acquired first impressions. But any belief, once acquired, is difficult to shake. If someone exposed to pre-trial publicity forms an opinion about who they think is guilty, that will serve as an initial belief that distorts the evaluation of any evidence they’re presented during a trial.

- Group dynamics within the jury: Once jurors are selected, they form a group characterized by features that render them particularly susceptible to maladaptive group dynamics (You can read more about why exactly that is in our previous article, “Avoiding Groupthink in the Jury Room”). The social pressure of group membership and a predisposition for confirmation bias create a perfect environment for group polarization. In jury deliberation, confirmation bias leads jurors to attend to the people expressing similar views or opinions selectively. When people discuss similar views, group polarization can occur, in which those pre-existing views are reinforced by this agreement and then become amplified or more extreme.

The Impact of Confirmation Bias on Litigation:

Confirmation bias can have far-reaching implications throughout the litigation process, affecting both the assessment of evidence and the decision-making of jurors in critical and deleterious ways:

- Biased processing of evidence and information: This outcome is a central hallmark of confirmation bias. Confirmation bias leads jurors to selectively focus on the evidence that supports their initial beliefs, potentially distorting their evaluation of evidence. If someone decides that they believe a person is guilty, all subsequent evidence will be interpreted to confirm that belief. One study demonstrated how confirmation bias distorts how evidence is evaluated by having participants read a mock police file containing only weak circumstantial evidence that pointed toward one potential suspect [6]. After reading this, some participants were asked to predict who they thought was guilty. As soon as they made their predictions, they went on to look for additional evidence and then interpreted that evidence in ways that confirmed their initial prediction. By the end, they evaluated this initially weak suspect as a prime suspect. Consider how this can be affected by pre-trial publicity or holding initial beliefs about groups of people that generate expectations for how they will behave. If a juror comes into the trial with a prediction about the outcome, all evidence will be viewed through the lens of that belief.

- Influence on witness credibility assessment: Jurors may disproportionately believe or discredit witnesses based on whether their testimony aligns with their preconceived notions. This can compromise the fairness of the trial, as witness credibility is a critical factor in determining guilt or innocence.

- The role of confirmation bias in juror deliberations and decision-making: By the time of deliberation, confirmation bias may have already affected their evaluation of the evidence and witness testimonies presented to a jury. It is, therefore, likely that if a juror held a case-relevant belief, those initial beliefs have been strengthened by the time deliberation begins. During the deliberation, jurors would be even more likely to cling to those beliefs and resist changing positions. If other jurors share those opinions, group discussions will reinforce existing biases to entrench those biases further and hinder objective decision-making.

Strategies to Mitigate Confirmation Bias:

There is not an easy solution to mitigate the effects of the “mother of all biases”. Addressing confirmation bias requires a multifaceted approach, involving a clear understanding of the underlying science, proactive measures during jury selection, and ongoing interventions throughout the trial process.

- Avoiding Attorney Biases – Scientific Jury Selection: As with most things, the first step is admitting you have a problem. No one with a human brain and its limited cognitive capacity is immune to cognitive biases, not scientists, jurors, or lawyers. Thus, avoiding your own biases by implementing rigorous jury selection processes that are derived from scientific and statistical approaches is critically important. Leveraging a team of behavioral scientists is an effective way to do this. Behavioral scientists possess expertise in the underlying science of confirmation bias and understand how to study human behavior effectively. In the beginning of this article, it was emphasized that all people are susceptible to confirmation bias. Behavioral scientists rely on the scientific method and statistics to study human behavior, rather than their own personal observations and theories, because the scientific method acts as a safeguard against errors such as confirmation bias. Psychology is a difficult science to communicate outside of the field because most people behave as intuitive psychologists.

One of the main reasons that pseudoscientific psychology is rampant amongst laypersons and within other disciplines is because confirmation bias makes these ideas easy to perpetuate. Psychology feels intuitive to people, so if you come up with a prediction about human behavior that sounds intuitive, it’s easy to convince others that your theory is correct. Once you convince others that your theory is legitimate, you have set the stage for belief perseverance. Advocates of an approach will selectively attend to any information that aligns with the approach and explain away any information that disconfirms it. Numerous “how-to” books on trial practice have touted pseudoscientific advice, masquerading as psychological research. Some of the resulting “psychological” claims include that cabinetmakers are meticulous and so will never be satisfied with the evidence, athletes won’t feel sympathy for anyone they perceive as fragile, people from Scandinavia will favor the prosecution, and you can determine a good juror by how much you like their face. Both psychological science and psychological pseudoscience make claims about human behavior and cognition, but they are distinguished by a very important factor: psychological science has safeguards in place to protect against the scientist’s confirmation bias, and psychological pseudoscience does not.

Trial advice derived from pseudoscience has never had to be tested objectively to determine whether or not it is accurate. Instead, people cite their own experiences, using their claims effectively to bolster their theory. However, by this point, hopefully, it has been established that once we have a belief, we are predisposed to only see what reinforces it. If a trial consultant developed an intuitive theory that claimed that athletes are not sympathetic towards an injured victim, what do you think would happen when they encounter a juror who is both an athlete and reports being very sympathetic towards an injured victim? Based on what we know of human psychology, they will not likely revise their theory based on disconfirming evidence. The more likely conclusion is that they will arrive at some justification that allows them to maintain their initial beliefs (“I only meant young athletes”, “That only applies to athletes who play team sports”, “They are exaggerating their sympathy – they just want to appear empathetic to the rest of the group but that does not reflect their real feelings”). Every time an athlete reports being unsympathetic, they will selectively attend to that and point to it as evidence for their theory. Every time an athlete does report feeling sympathetic, that evidence will be explained away or disregarded. What would make such a claim a scientific one would be if data were collected and relied on to arrive at that claim, taking one’s personal biases out of the equation.

Confirmation bias affects not only the development and propagation of pseudoscientific approaches to trial practice but also how a trial lawyer evaluates prospective jurors during jury selection. If a trial lawyer goes into oral voir dire with an intuitive, rather than scientific, approach to jury selection, they will approach potential jurors with a predetermined set of expectations. In one study [2], attorneys were given juror profiles and asked to create an oral voir dire strategy based on those profiles. The results indicated their expectations were used to formulate intuitive theories about those jurors. Their voir dire strategies involved asking questions to confirm their theories, ultimately leading to conclusions biased by the questions they asked. They heard what they expected to hear because they asked questions designed to prove they were right. Given what we know about confirmation bias, it is probably unsurprising that an intuitive approach to jury selection is ineffective. Although it would be advantageous for attorneys to accept the evidence that most lawyers cannot effectively predict how jurors will vote, either based on their intuitive rules of thumb [7] or how they interpret prospective jurors’ responses during oral voir dire [8, 9].

Effective and accurate behavioral research and jury selection both require the same basic considerations, which makes the expertise of behavioral scientists powerfully applicable to jury selection. Both require an understanding of human psychology, expertise in applying the requisite research methodology to human behavior, and the capability to collect and analyze the data required for objective and valid conclusions.

- Applying effective jury selection techniques: The previous criticism of intuitive approaches to jury selection was only criticism of the approach, not the goal. Intuitive and scientific approaches to jury selection both use juror characteristics to predict trial outcomes. However, the intuitive approach to jury selection is subject to cognitive biases and relies on subjective impressions and stereotypes. The scientific approach to jury selection implements safeguards against human bias and uses objective methods. Crucially, the scientific approach recognizes that whether a juror characteristic predicts trial outcomes depends on the specifics of each and every case [10]. Pre-trial research based in behavioral science can be used to collect data that can be assessed using predictive analytics to explore statistical relationships between demographic and psychographic factors and attitudes relevant to a particular case. These results can be used to develop scientifically validated questions to be included on a supplemental juror questionnaire (SJQ) to screen for prospective juror’s biases, which help mitigate the likelihood that verdicts are affected by confirmation bias. The results can also inform oral voir dire strategies. Questions can be developed based on objective data rather than confirmation bias, and those questions can be used to more accurately identify individuals who exhibit strong biases that could undermine impartiality.

- Jury Instructions and Interventions: Remember, the first step to safeguarding against confirmation bias is admitting you are vulnerable to it, so educating the jury about this issue is important. Providing clear instructions to jurors about impartiality and highlighting the risks of confirmation bias can foster awareness and counter its effects during the trial. Ideally, a short informative video designed by psychologists could be shown to jurors before a trial. Judges can also remind jurors to remain open-minded, critically evaluate evidence, and consider alternate perspectives.

- The role of legal professionals: Lawyers and judges play a critical role in recognizing confirmation bias and actively addressing it through strategic questioning, cross-examination, and jury instructions. Legal professionals can encourage jurors to engage in more objective decision-making by challenging jurors’ biases through compelling arguments and evidence.

Future Directions and Recommendations:

Continued efforts are needed to advance the understanding of confirmation bias and develop evidence-based strategies to minimize its impact on the legal system.

- Technology-assisted jury selection: Exploring the use of artificial intelligence (AI) technology to assist in jury selection can significantly improve the integrity of the process. Algorithms can be developed to analyze a wide range of data, including demographic and psychographic information and case-specific information, to minimize bias and increase diversity in jury composition. Leveraging data and predictive analytics can help identify potential biases, allowing for a more informed and objective selection process. Additionally, AI tools can provide real-time feedback to legal professionals during jury selection, highlighting potential biases and ensuring a more representative and unbiased jury.

- Incorporating psychological insights into legal training and practice: Integrating social psychology and quantitative methods knowledge into legal education and training can equip legal professionals with a deeper understanding of confirmation bias and other cognitive biases. AI can play a role in this by using AI-powered chatbots, which can engage in dialogue with legal professionals and provide feedback that enables them to navigate the complexities of jury selection and trial advocacy with greater awareness of their biases.

- Advancing research on confirmation bias and its impact on litigation: Continued research on confirmation bias and its effects on jury selection and trial outcomes can provide further insights and inform evidence-based strategies for bias mitigation. Collaborations between social scientists, legal scholars, and practitioners can foster a more comprehensive understanding of confirmation bias within the legal context.

Conclusion:

Confirmation bias poses a significant challenge within the legal system, influencing jury selection and the overall fairness of trial outcomes. By understanding the psychological mechanisms behind confirmation bias and implementing strategies to mitigate its effects, legal professionals and jury analysts can enhance the integrity and impartiality of the legal process. Recognizing the relevance of confirmation bias and working towards its mitigation will pave the way for a fairer and more equitable legal system for all.

References

- Gilovich, T., & Ross, L. (2016). The wisest one in the room: How you can benefit from social psychology’s most powerful insights. Simon and Schuster.

- Otis, C. C., Greathouse, S. M., Kennard, J. B., & Kovera, M. B. (2014). Hypothesis testing in attorney-conducted voir dire. Law and Human Behavior, 38(4), 392.

- Dror, I. E. (2016). A hierarchy of expert performance. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 5(2), 121-127.

- Darley, J. M., & Gross, P. H. (1983). A hypothesis-confirming bias in labeling effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 20-33.

- Ruva, C. L., & Guenther, C. C. (2015). From the shadows into the light: How pretrial publicity and deliberation affect mock jurors’ decisions, impressions, and memory. Law and Human Behavior, 39(3), 294-310.

- O’Brien, B. (2009). Prime suspect: An examination of factors that aggravate and counteract confirmation bias in criminal investigations. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 15(4), 315-334.

- Olczak, P. V., Kaplan, M. F., & Penrod, S. (1991). Attorneys’ lay psychology and its effectiveness in selecting jurors: Three empirical studies. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6(3), 431.

- Kerr N. L., Kramer, G. P., Carroll, J. S., & Alfini, J.J. (1991). On the effectiveness of voir dire in criminal cases with prejudicial pretrial publicity: An empirical study. American University Law Review, 40, 665-701.

- Zeisel, H., & Diamond, S. S. (1978). The effect of peremptory challenges on jury and verdict: An experiment in a federal district court. Stanford Law Review, 491-531.

- Seltzer, R. (2006). Scientific jury selection: Does it work?. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(10), 2417-2435.